Albanian men are rolling dice in the alley of the hostel where I’m staying.

I’ve met men from across Africa and the Levant staying in hostels over the past three days: from Egypt, Libya, Syria.

Of course, there’s Americans and Europeans and other sorts of travelers, too. Even this time of year. There’s always people traveling like this. They’re from California, Croatia, Canada, Germany, Italy, New Zealand, etc.

The days are short, and it was sunny but it’s raining for the next two days. It gets dark early. It’s two time zones west of Izmir. The flight from Istanbul was shorter than the elapsed time. I landed five minutes before my flight took off, local time.

I missed my Turkish connection because it was impossible, and on top of that I wasn’t able to leave the country without stamp since I overstayed my ninety-day limit by twelve hours. But after a delay, it’s okay.

In Tirana—Tiranë—now. I’m learning a lot about a country’s history I don’t know much about. It once was the far western edge of the Ottoman Empire, in Europe. The African Ottoman Empire reached as far west as Morocco. In Europe, Albania was once was part of the Roman Empire, its proximity across the Adriatic from Italy means an Italian influence still lingers. For instance, I feel the disappointment across the counter whenever I order any coffee that’s not an espresso or a macchiato.

Yet there’s also plenty of raki, and it is raki, not ouzo. They use other Turkish words. The restaurant near my hostel is called “oda,” and Mother Teresa’s name, as I learned from my walking tour guide, was Gonxhe, an Albanian name that sounds close to and has the same meaning as its Turkish origin and likeness, gül, a root meaning rose1. Her likeness is depicted outside and inside the Catholic church.

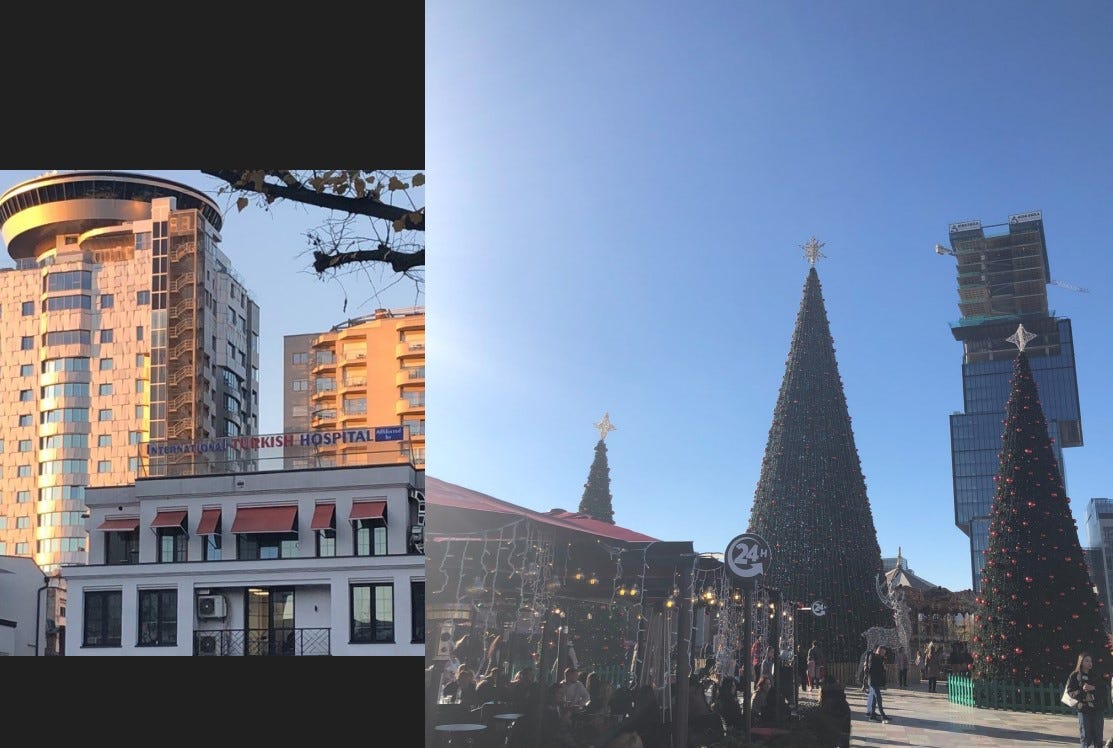

It’s now one of Europe’s freshest and quickest modernizing non-EU travel destinations, thanks in large part to EU-financing. Being about 50.1% Muslim, with the rest of the population Albanian Orthodox Christian, Catholic, atheist, or something else non-affiliated or in between, it feels more like the demographic mixture than most places, at least religiously—which reminds me of home.

Despite all the occupations—or because of them—there’s a religious harmony and “softness” and respect under the national flag of Albania. It was an atheistic nation—the first one—for a while. Perhaps that allowed such a hardcore communism to run rampant for decades in the 20th century.

The symbol on the flag is a black eagle with Ancient Roman origins. The Roman aquila, or eagle, was a powerful, quasi-religious (identity-binding) symbol. But the Albanian one has two heads2: one looking west and one looking east. If you’ve been subscribed and reading for a while, you can see a pattern in what I notice in the places I visit. If you’re new here: the theme of East-meeting-West emerges and keeps coming back again.

The crossroads that Albania occupies is one of intersecting and clashing cultures: between the Roman imperial poles of Rome and Constantinople. It’s part of a geography occupied not only by Romans, but by Ottoman Turks, with some conflict with Venetians in between, and with Germans and Italians after that. Yet it’s also Balkan, but apart from the Balkans. Like Greece, it’s Balkan but kind of not Balkan. It was never Yugoslavic.

The language, Albanian, is distinctly Albanian. It has its own root but also has adopted words and patterns from other nearby languages: Roman, Turkic, Greek, Slavic. Like Greeks call themselves Έλληνες (Hellenes) and Greece Ελλάδα (Elláda), Koreans 한국 (Hanguk), the Chinese 中國 (Zhōngguó), and so on, Albanians are shqiptarët and Albania is Shqipëria.

Most of the young people speak English well, and it’s easy to order things and interact. Islam feels “softer” here in its presence, but I have little idea what people actually believe. This is how people have described it, and something like how interactions feel different. There are many building projects: skyscrapers, new hotels, museum renovations, a new Orthodox church. New development is everywhere. My walking tour was 95% English and British attendees. I guess there’s some travel trends going on among the peripheral EU3.

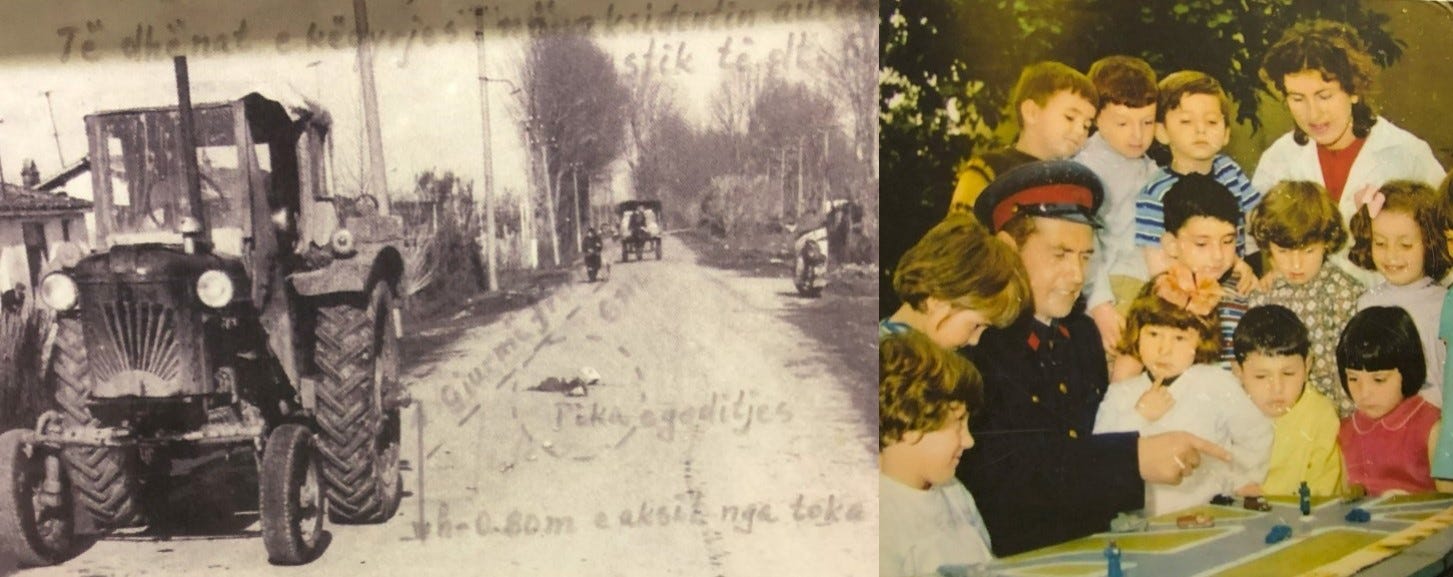

People amble slowly and zigzaggedly on the narrow sidewalks, which reminds me largely of how older pedestrians walked in South Korea. The older generation lived through hard times, and presently modernization has happened rapidly, in both places. Albania struggled through a complicated, totally oppressively communistic Yugoslav-adjacent Balkan history until the late 90s. It’s been an independent republic since 1912, breaking from the Ottoman Empire, only to have to fend for itself during the world wars, but only emerged from total communist rule with elections in 1991, and from further international peacekeeping in the late 90s.

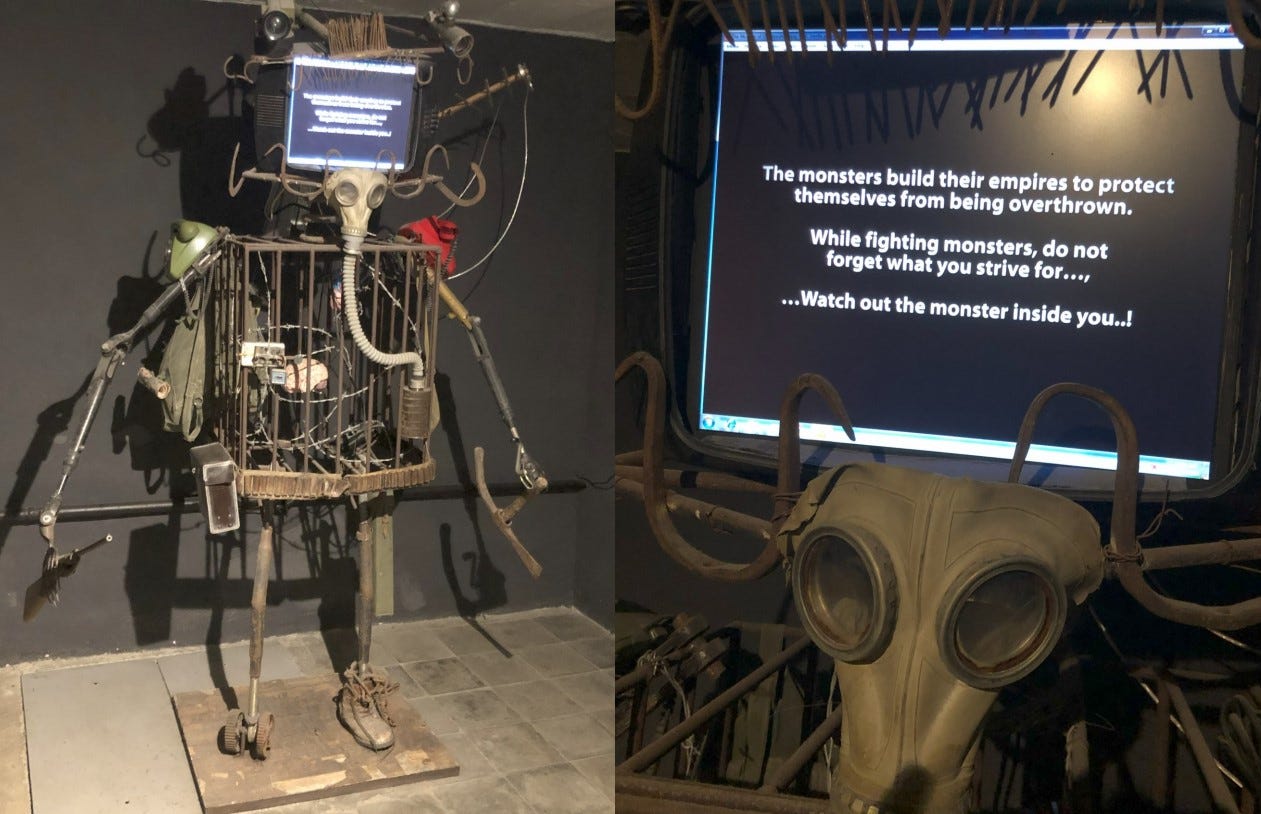

I learned a lot about its isolated, communist history in the bunker museum, built in an old anti-nuclear fallout bunker. These bunkers were built out of the fears of another invasion but never used, because no one invaded since their inception. My walking tour guide said people would refer to Albania as the “North Korea” of Europe. As the museum narrative also shows: tight state control, suffocating surveillance and domineering forces were dehumanizing and cruel.

I’ve only had a few days of learning about a place I know next to nothing about. The flag is omnipresent, but not as ubiquitous as the Turkish flag in Türkiye. Yet that eagle symbol, with its mysterious power and two heads, is pretty common. You don’t see this nationalistic symbol-thing present in all countries, not as much as in Türkiye or in Albania. In Türkiye it is the flag and Atatürk. In Albania, it’s mostly this symbol.

Something about the unique image of the black and red Albanian flag signifies strength and something palpably vestigial. With Atatürk’s profile in Türkiye, it feels more like a powerfully patriarchal presence. This sacred two-headed eagle has a mystique to it. It’s everywhere. It even glows from behind the bulbs of the pedestrian street crossing lights.

Mornings and early afternoons are sunny, but besides that it’s been rainy. A Christmas carnival and fair occupies the city’s center. KFCs and Popeye’s are omnipresent, which is surprisingly comforting even though I don’t typically eat at these places. Like

’s paean to McDonald’s, I find visiting KFCs a comforting, grounding experience. Also: local fast-food places like Opa, where I wrote part of this essay fueled by gyros and Greek style pita.The relics of the past remain alongside many modern projects. Many bunker entrances are sprinkled around the city, apparently never used since they were built only after millennia and centuries of occupations and conflicts, when the greatest enemy came from within in the form of despotic communist leadership. People are still working out the norms of traffic and sidewalk and bike lane use. It’s nowhere near as chaotic as Vietnam or other places in Africa and Asia, but still you’ve got to watch out for the periodic red-light transgressors, unpredictable lane-changers, sidewalk cyclists, and against-traffic bikers. The road rules seem fairly normal but slightly off-kilter.

The founding hero of Albania is a fifteenth century Ottoman-trained soldier named Gjergj Kastrioti Skanderbeg. Skanderbeg is his Ottoman Turkish name, which he kept after defecting from the Turks back to Albania, after being taken and trained as a child. He kept his Turkish name, Skanderbeg, which actually comes from Turkish through the Hellenistic expansions led by Alexander the Great, who was Macedonian. Skander, Iskender, and such are Turkic versions of Alexander. One could argue, as I imagine many Albanians do, that the Macedonian origins of Alexander the Great—like Mother Teresa—are more closely rooted to Albania than to the Hellenistic Greece of Sparta and Athens, much further south of Macedonia. So the narratives of history goes on, adapted to whoever tells the story. Gjergj (George) Skanderbeg used the double-headed eagle as his symbol. The same one central to the Albanian flag and pedestrian crosswalk lights.

The currency, lek, derives its name from Aleksander, via Skanderbeg. I have yet to visit a money changer, but most transactions prefer cash over cards here. I’ve used American dollars to tip and Euros to pay for food at the Christmas fair. I’ll have to convert some cash soon. It’s always fun to see what a new currency looks like and read what it says, see who it depicts on their bills and coins. Lek looks colorful, to say the least.

I have a future essay in me about the ubiquity of Atatürk’s profile in Türkiye, not just his face etched on budlings and on flags and banners, but his face on the front sides of every denomination of paper currency and hung on banners and displayed inside homes and bookstores, and in every commercial business prominently—and handsomely. It’s been one hundred years, but in Turkey the presence of the republic’s founder is still noticeably everywhere, and powerfully so.4

There’s more interesting things I could go on about: the piece of the Berlin Wall standing in the park, the espionage hub known as the House of Leaves, the Albanian Orthodox Church built like a mosque, Kosovo (which I have yet to visit), etc. But I’ll stop short and just leave it to the pictures.

Thanks again for staying with me.

I will probably cross-post this travel-centric essay to my other blog, Explorations, next Tuesday.

ARW

One of the strangest word etymologies actually traces the English word, rose, to a Turkish source, gül. The English, from the Greek rhodon, is close enough to resemble likeness in spelling and sound. But the Greek, from the Iranian or Persian root vrda leads some linguists to argue that, like the flower, rose comes from the East. In Armenian, it’s vard. In Aramaic, warda. In Old Persian, gul. If modern Persian cognates come from Old Persian with a sound change, then the source well could be the Turkic gül. (OED)

The Serbian flag, and Air Serbia, also depicts a two-headed eagle. Serbia and Albania still may be a little raw about Kosovo, but like Greece and Türkiye, the conflicts overlap with cultural similarities.

Albania is in trajectory to join the EU in four or five years, versus the UK, which already left.

Standing on a tram once, I noticed a girl and her father. She was playing a game with herself by pointing and announcing every time she saw Atatürk’s face anywhere from inside the tram, through its large windows as it passed through the city.

"Bunker 2" should read "BunkArt 2" ... there's also a BunkArt 1, which is a multi-story bunker several miles outside the city.